The only irreplaceable capital an organization possesses is the knowledge and ability of its people. The productivity of that capital depends on how effectively people share their competence with those who can use it."

––Andrew Carnegie

Between 1644 and 1737, in the small northern Italian town of Cremona, lived Antonio Stradivari, who made over 1,000 violins, violas and cellos; a harp; and a couple of lutes that bear his famous name. These instruments are the most sought-after, and expensive, in the world, regularly selling in the millions of dollars.

Today, even with all the advances in modern technology we still cannot replicate the musical quality of an instrument handcrafted over 300 years ago. The knowledge—known as “the Stradivarius secret”—has been lost.

With the so-called Graybe Boom, the average age of the workforce in the rich world is increasing at the same time many of the Boomers are anticipating retirement, making them the first wave of knowledge workers to do so.

Companies lose knowledge from people leaving, forgetting, retiring, and so on. Knowledge also becomes obsolete (what Alvin Toffler calls obsoledge) and must be constantly replenished. No one knows what the cost of this lost knowledge might be. Given the coming demographic trends, how can knowledge organizations capture some of that valuable knowledge before it is lost, like the lost Library of Alexandria?

Before we can leverage this knowledge, we must first understand how knowledge is possessed.

We Know More Than We Can Tell

A teacher tells one of his pupils to write a letter to his parents, but the student complained: “It is hard for me to write a letter.” “Why! You are now a year older, and ought to be better able to do it.” “Yes, but a year ago I could say everything I knew, but now I know more than I can say.”

Michael Polanyi, drew a distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge. To illustrate tacit knowledge, he said, try explaining how to ride a bike or swim. You know more than you tell.

Tacit knowledge is “sticky,” in that it is not easily articulated and exists in people’s minds. It is complex and rich, whereas explicit knowledge tends to be thin and low-bandwidth, like the difference between looking at a map and taking a journey of a certain terrain. It is the difference between reading the employee manual and spending one hour chatting with a coworker about the true nature of the job and culture of the firm.

Explicit is from the Latin meaning “to unfold”—to be open, to arrange, to explain. Tacit from the Latin means “silent or secret.” Try describing, in words, Marilyn Monroe’s face to someone, an almost impossible task, yet you would be able to pick her out among photographs of hundreds of faces in a moment.

Germans say Fingerspitzengefühl, “a feeling in the fingertips,” which is similar to tacit knowledge. The French say je ne sais quoi (“I don’t know what”), a pleasant way of describing tacit knowledge. The highest levels of knowledge and competence are inherently tacit, being difficult and expensive to transmit.

This type of knowledge transfer is a “social” process between individuals, and is especially important in knowledge organizations where so much of the intellectual capital (IC) is “sticky” tacit knowledge.

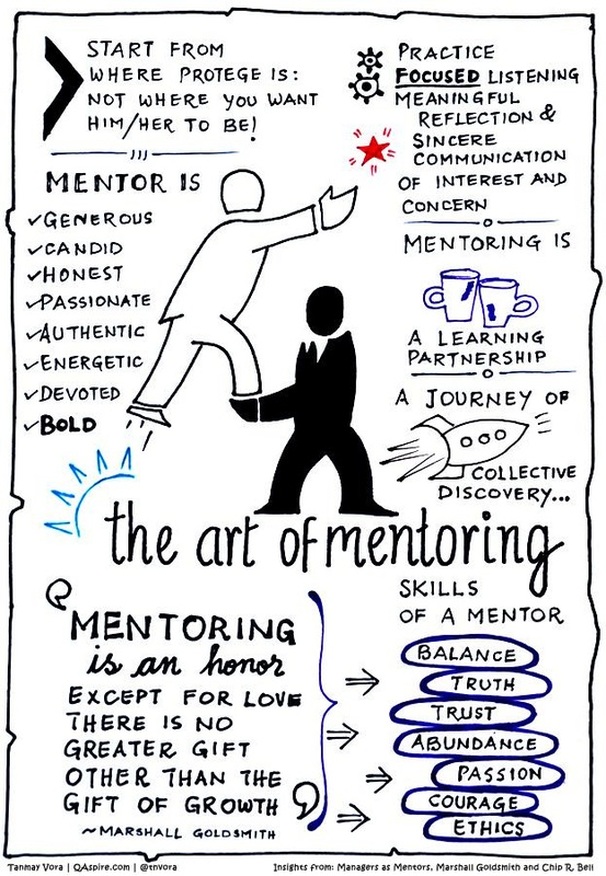

I seen the below on LinkedIn today, it led me to thinking - what better to ensure that knowledge is transferred than to develop real and meaningful mentoring networks to ensure that tacit knowledge is not lost to the next generation.

––Andrew Carnegie

Between 1644 and 1737, in the small northern Italian town of Cremona, lived Antonio Stradivari, who made over 1,000 violins, violas and cellos; a harp; and a couple of lutes that bear his famous name. These instruments are the most sought-after, and expensive, in the world, regularly selling in the millions of dollars.

Today, even with all the advances in modern technology we still cannot replicate the musical quality of an instrument handcrafted over 300 years ago. The knowledge—known as “the Stradivarius secret”—has been lost.

With the so-called Graybe Boom, the average age of the workforce in the rich world is increasing at the same time many of the Boomers are anticipating retirement, making them the first wave of knowledge workers to do so.

Companies lose knowledge from people leaving, forgetting, retiring, and so on. Knowledge also becomes obsolete (what Alvin Toffler calls obsoledge) and must be constantly replenished. No one knows what the cost of this lost knowledge might be. Given the coming demographic trends, how can knowledge organizations capture some of that valuable knowledge before it is lost, like the lost Library of Alexandria?

Before we can leverage this knowledge, we must first understand how knowledge is possessed.

We Know More Than We Can Tell

A teacher tells one of his pupils to write a letter to his parents, but the student complained: “It is hard for me to write a letter.” “Why! You are now a year older, and ought to be better able to do it.” “Yes, but a year ago I could say everything I knew, but now I know more than I can say.”

Michael Polanyi, drew a distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge. To illustrate tacit knowledge, he said, try explaining how to ride a bike or swim. You know more than you tell.

Tacit knowledge is “sticky,” in that it is not easily articulated and exists in people’s minds. It is complex and rich, whereas explicit knowledge tends to be thin and low-bandwidth, like the difference between looking at a map and taking a journey of a certain terrain. It is the difference between reading the employee manual and spending one hour chatting with a coworker about the true nature of the job and culture of the firm.

Explicit is from the Latin meaning “to unfold”—to be open, to arrange, to explain. Tacit from the Latin means “silent or secret.” Try describing, in words, Marilyn Monroe’s face to someone, an almost impossible task, yet you would be able to pick her out among photographs of hundreds of faces in a moment.

Germans say Fingerspitzengefühl, “a feeling in the fingertips,” which is similar to tacit knowledge. The French say je ne sais quoi (“I don’t know what”), a pleasant way of describing tacit knowledge. The highest levels of knowledge and competence are inherently tacit, being difficult and expensive to transmit.

This type of knowledge transfer is a “social” process between individuals, and is especially important in knowledge organizations where so much of the intellectual capital (IC) is “sticky” tacit knowledge.

I seen the below on LinkedIn today, it led me to thinking - what better to ensure that knowledge is transferred than to develop real and meaningful mentoring networks to ensure that tacit knowledge is not lost to the next generation.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed